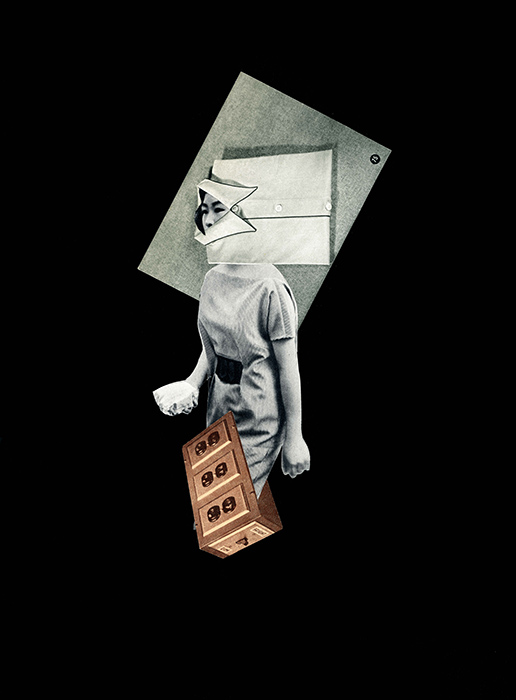

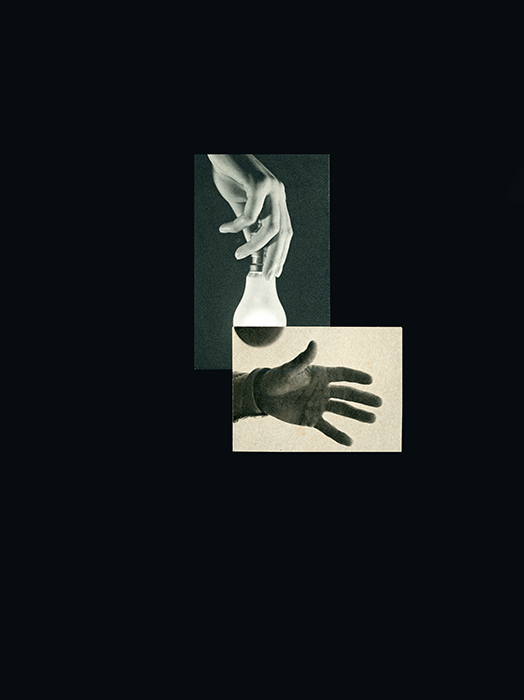

German Dada artist Hannah Höch was among the originators of photomontage in the years following World War I, a technique based on the creation of new pictures from existing, mainly photographic, images extracted from magazines, newspapers, and other printed matter, which are cut-and-pasted, combined, and manipulated, much like collage. The Dada artists made photomontage a major vehicle to disseminate criticism and protest, as it enabled decontextualization and defamiliarization of reality documentation, imbuing it with nonsense and absurd aspects.

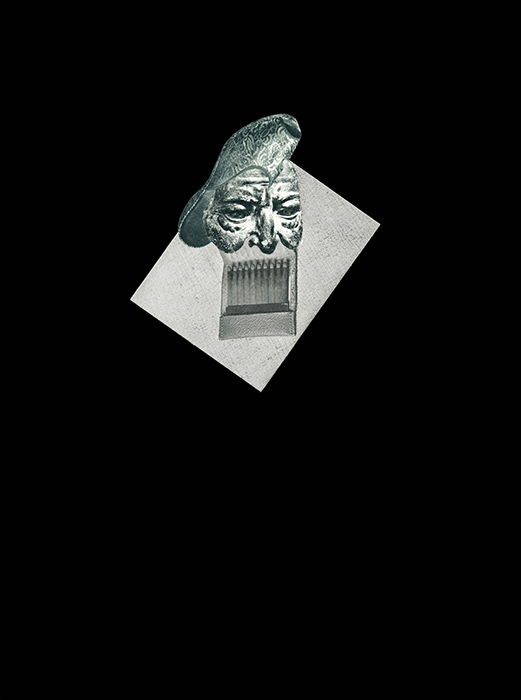

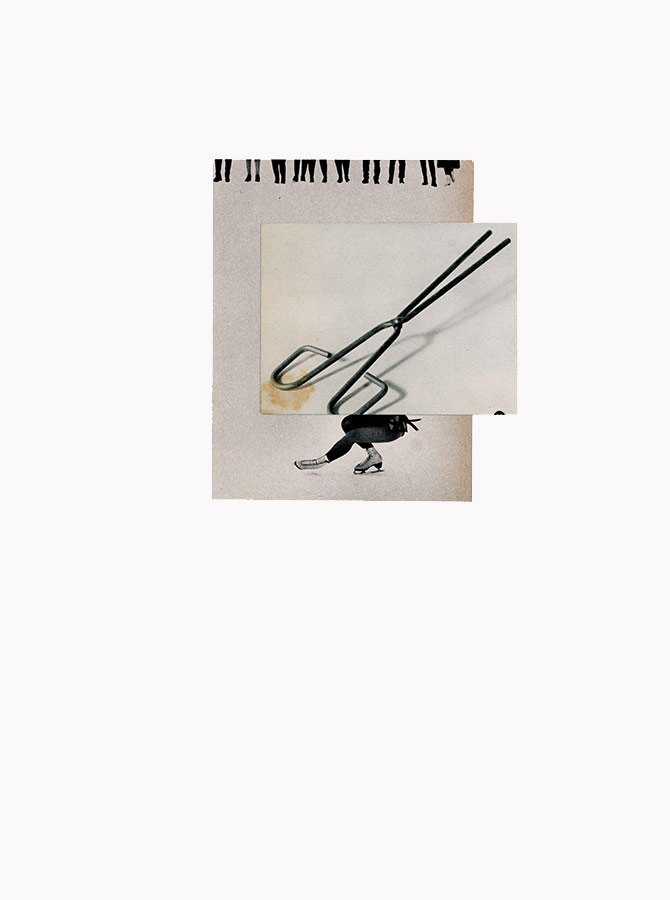

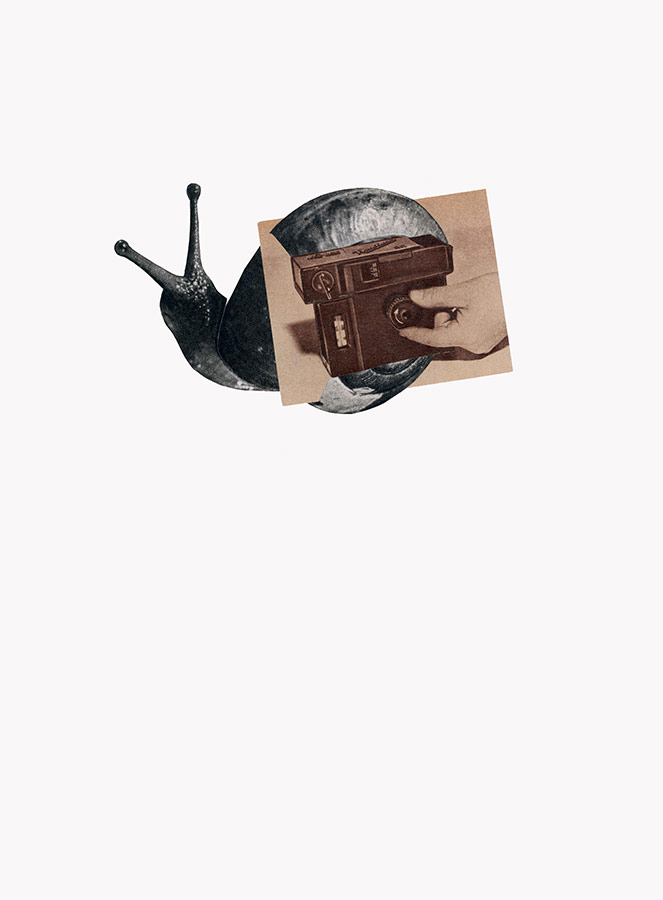

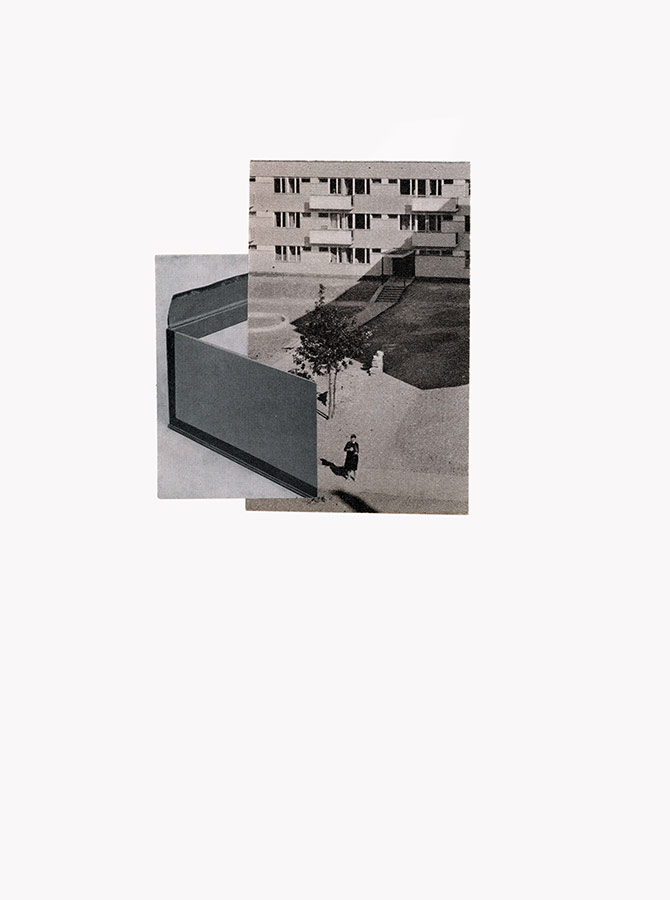

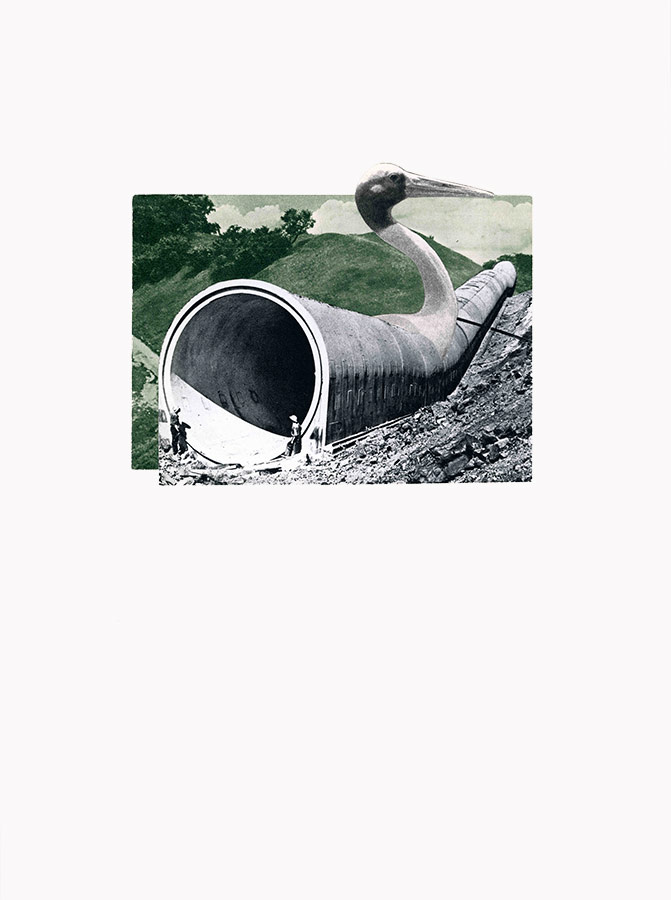

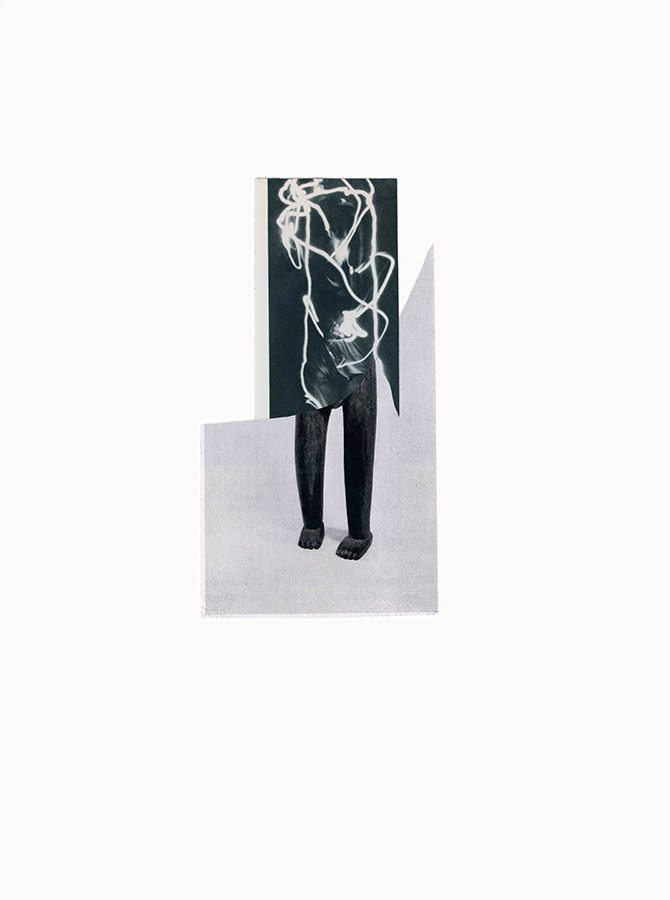

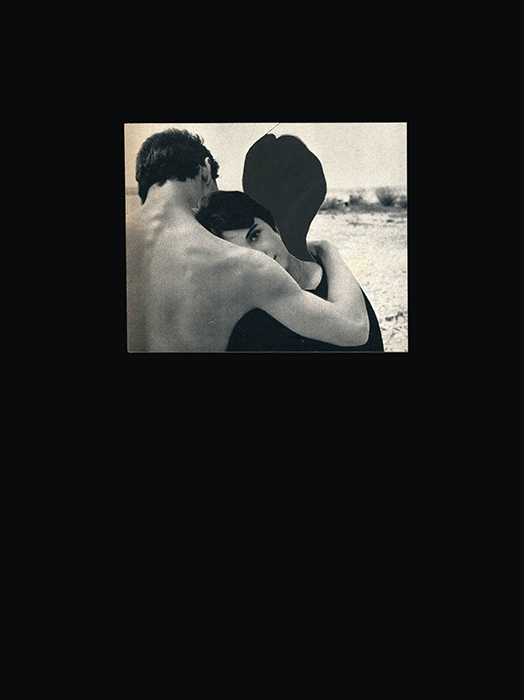

Shay Zilberman, who shares his date of birth (1 November) with Höch, has been conducting a long dialogue with the techniques of modernist collage, Dadaist photomontage, and printmaking, including Höch’s work. He uses these practices to form artistic modes reminiscent of those of an archaeologist and a researcher of contemporary culture. He maps the printed photographic images of the 20th century, culls and collects them, subsequently stitching them together surgically by cutting and pasting, to form a new work that reveals invisible realms, while concurrently criticizing the modernist concept of the present. Unlike the spirit of Dada, Zilberman’s works are imbued with 21st century melancholy with regard to modernity and with reflections on the relations of continuity and rupture between man and the environment. They invite the viewer on labyrinthine journeys in confined spaces, while observing man being reflected and swallowed-spawned in the infinite mirrors between reality and dream.

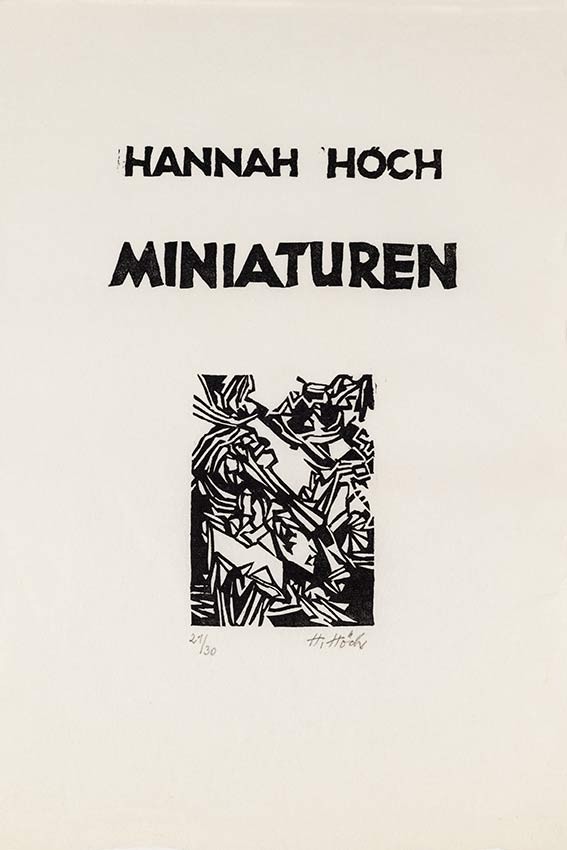

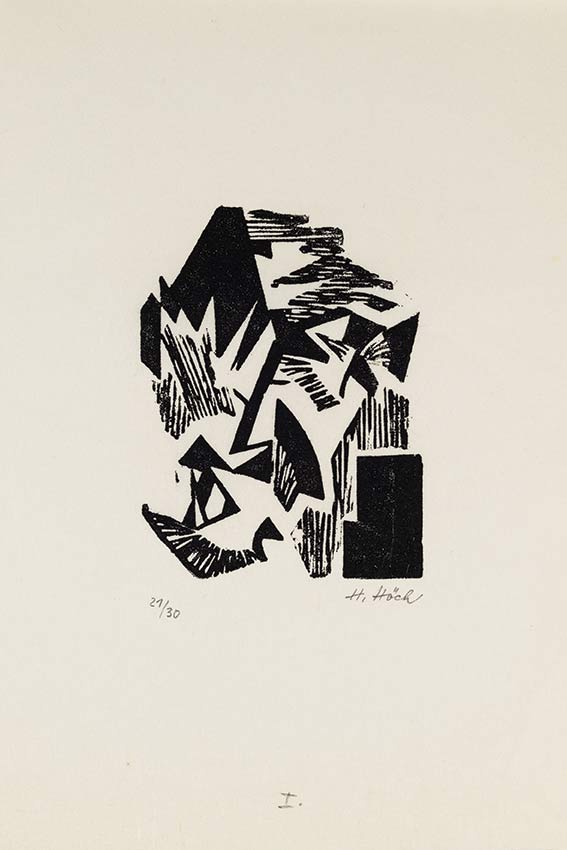

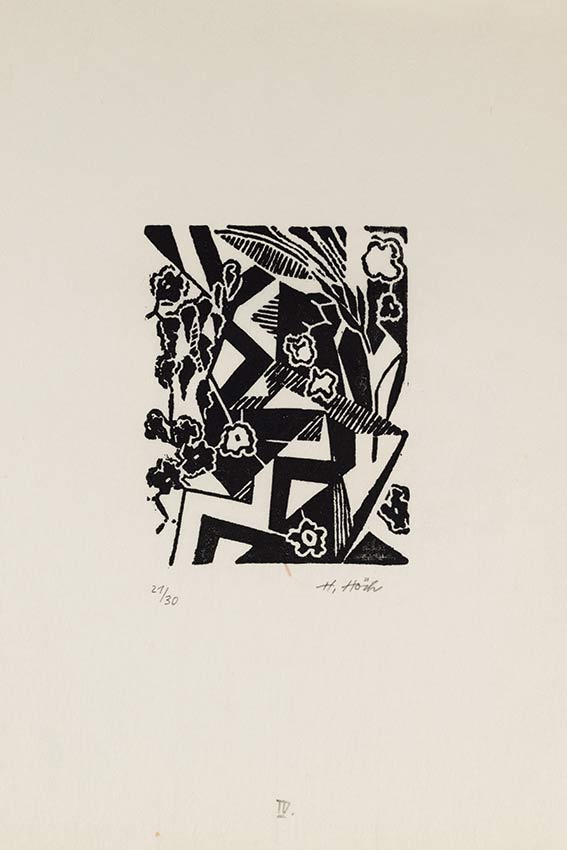

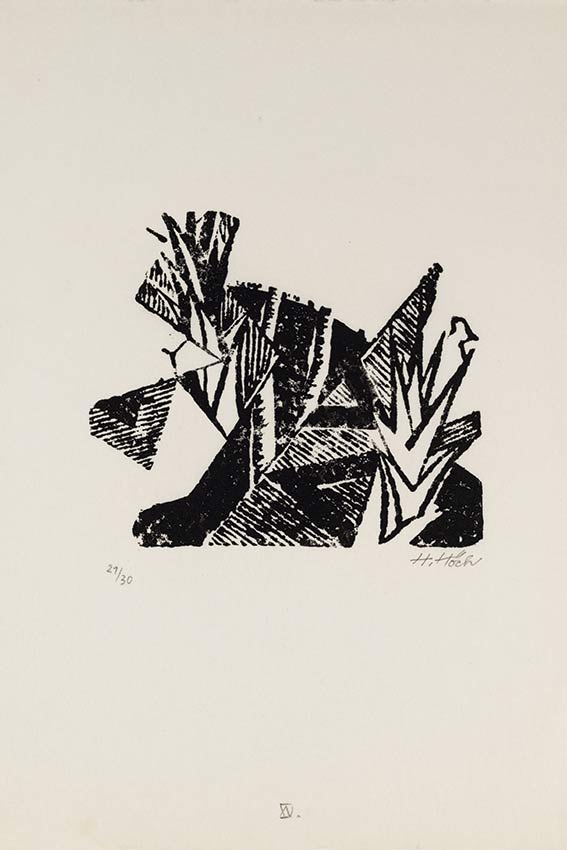

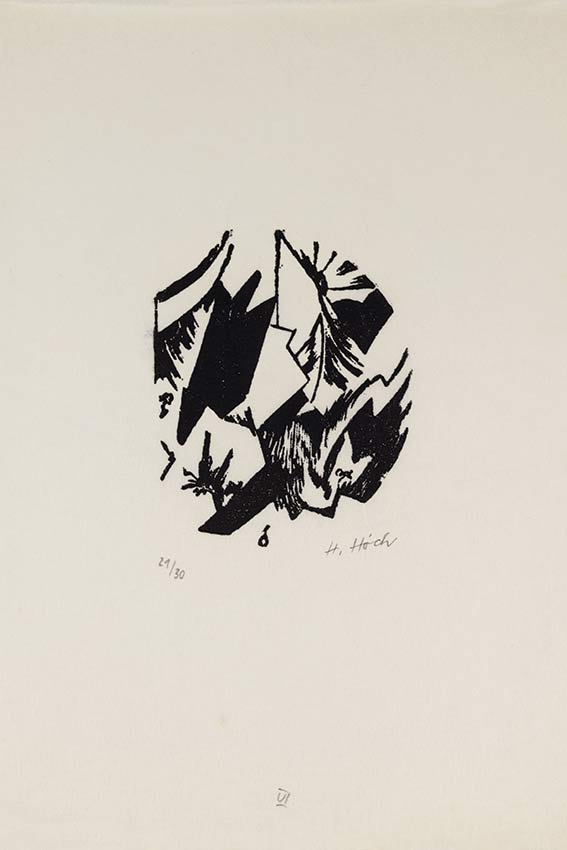

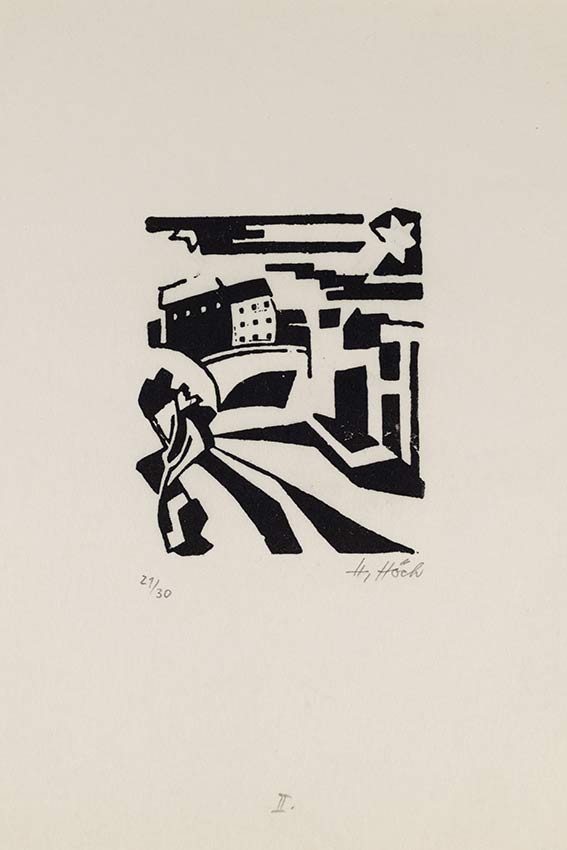

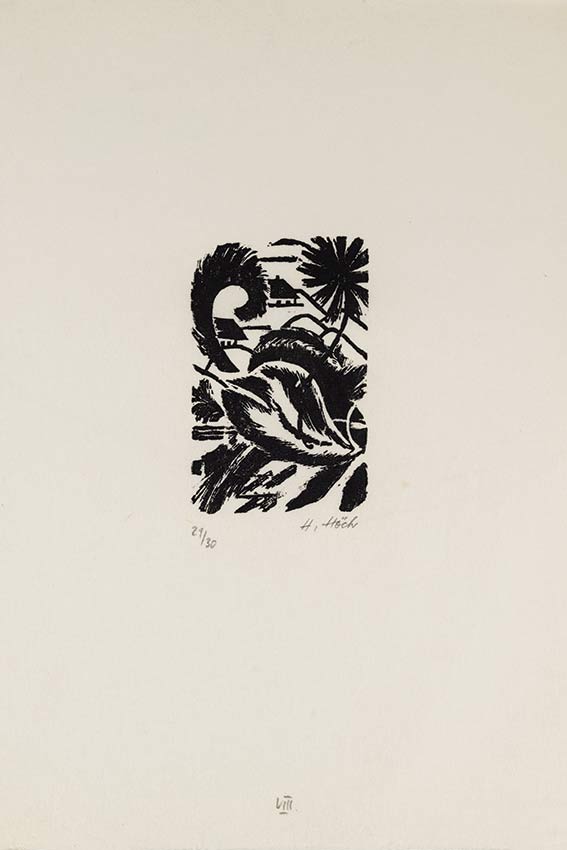

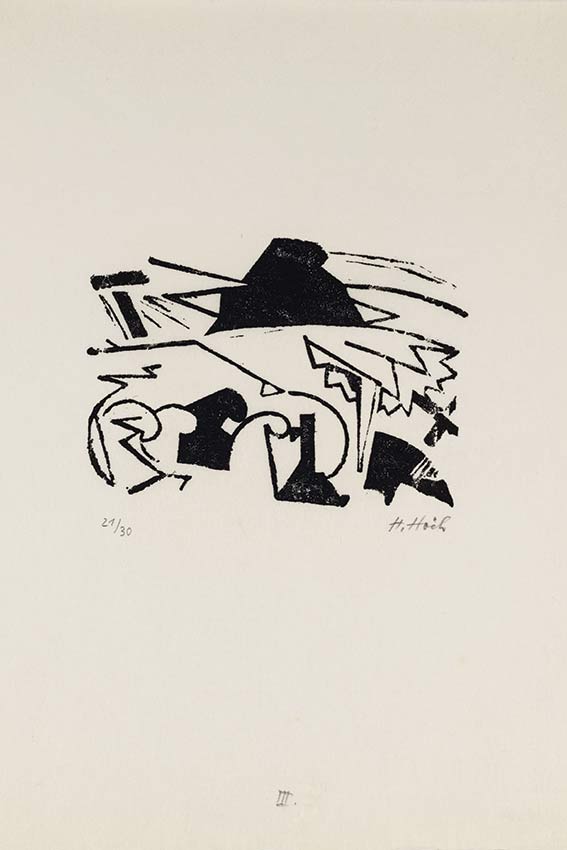

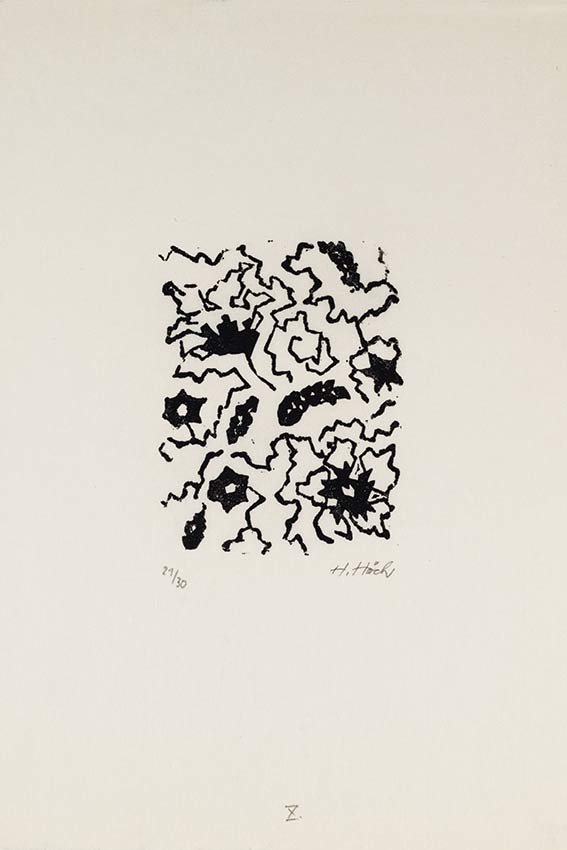

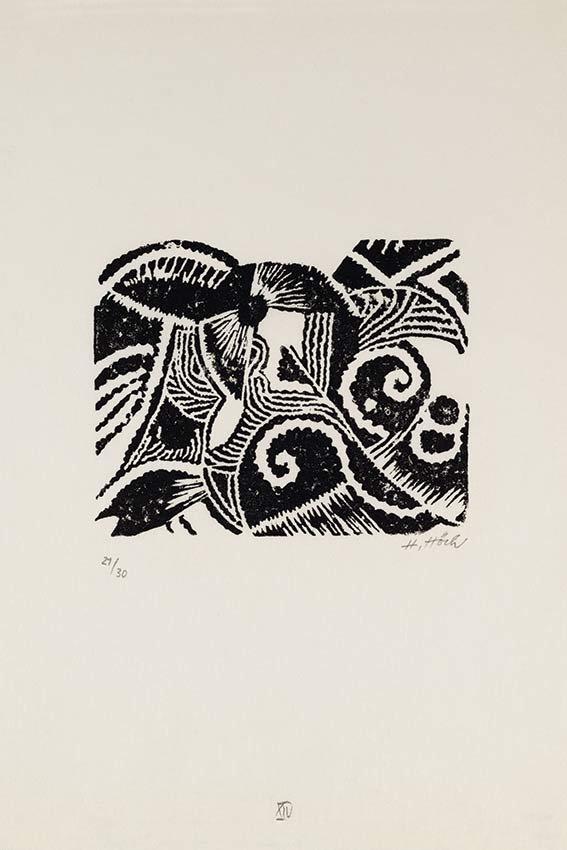

Höch’s linocut album was created early in her career (1915-1918), almost concurrent with the years in which she honed the photomontage technique. The works most identified with her, created in the 1920s during the Berlin Dada days, were characterized by anti-bourgeois and gender political criticism, including a surrealistic-humorous engagement with the woman’s body and place in German society of the time. The album’s prints represent another facet of her oeuvre: compositions originating in the figurative, which reach the abstract; ornamental, expressive miniatures that capture the formal harmonies of a landscape.

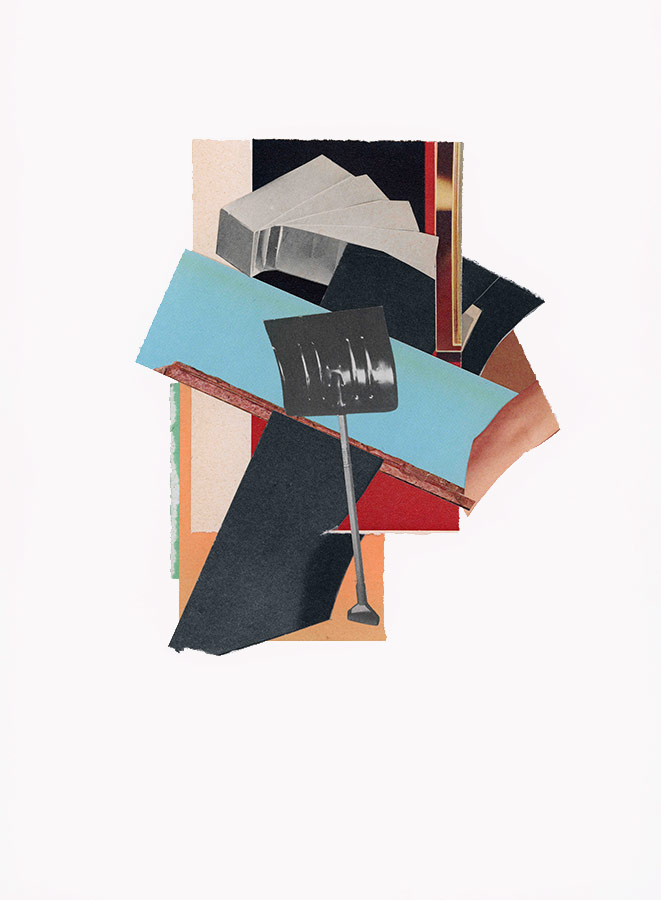

Höch worked for about a decade as a graphic designer for handicraft magazines, and the textile-related thinking of weave and pattern is evident in her work, as well as in the early photomontages, and especially in the linocuts. Zilberman, who after studying at the Beaux-Arts de Paris attended the Fashion Department at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Antwerp, presents new works that converse with the linocuts in the album Miniatures belongs to The Israel Museum collection. These works—partly abstract compositions from layers of colored paper—echo modern embroidery and textiles, with an occasional image popping out of them. These are juxtaposed by monochromatic figurative compositions, in which the human, the animal and the vegetal are intertwined. Zilberman’s works engage in an intimate dialogue, which converges into miniature compositions, while extending over historical and personal time. The time of the imagination and memory seems to be physically present in the space of the paper, as though the medium, the form, and the image try to forget their initial modes of creation, so they may be reborn and thus produce a different view of the world.

Curator: Irena Gordon